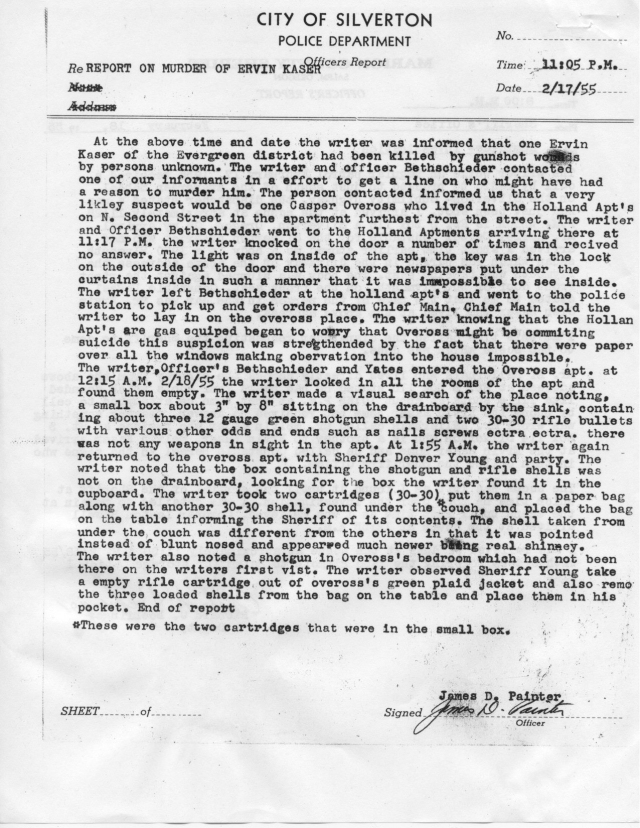

This is the third and final part about Ervin’s life and working on the hop farm. Next time: The Night of the Murder.

Calvin Kaser remembers:

Ervin was married to a Lucille Dixon in about ’33 or ’34. It didn’t last very long, I think it only lasted a few months. I think they were living at his place then. And then it wasn’t very long and she moved out, and then this Marian moved in, and she was there for maybe a year, then she moved out, and then he married Mary Callavan or Huntley.

Ervin was grumpy. Any little thing didn’t go right and, “Goddammit, don’t ya know what the hell you’re doin’?” and he’d cuss at the people, even the workers that were working for him. I remember, Brian Potter, was working for him in the hop yard putting irrigation pipes together. Of course, it was pipes that Ervin had made, and he got on Brian’s ass for not being able to get them together. Brian told me about it later. He said, “Well if you know so much about it, why don’t you come and fit this son of a bitch together!” Well, there was something about the rubber on the inside that wasn’t working right, it hadn’t fit into this shell that Ervin had made so it’d seal the water. Well, Ervin couldn’t get it together either, but that’s the way he was, he was quick tempered. Ervin and Melvin were similar in that respect. But Ervin, if he wanted something, it was nothing but pure milk and honey.

Very seldom did she do this, but when Mom made up her mind that enough was enough, by god Dad knew it. And when she said, “Enough is enough,” by god it was enough, there was just no two ways about it. She never swore very much, she might say ‘damn’ once in a while, or when she was referring to someone who was a dead-beat, she might say, ‘shit-ass’, I can remember her saying that once in while, but not very often.

I remember when I was a teenager [latter half of the 1930s], working in the hop yards at home, and Ervin had rented this hop-yard up in Jordan Valley, up around Scio, it was 30 acres up there. And that was another time that Ervin came back and Dad welcomed him with open arms, and it didn’t matter how many times Ervin shit on the folks, Dad always took him back, well, Mom, too. Well, he came back, and he could rent this hop yard up there, and it was a fruggles yard, it was the early hops, and it wouldn’t be any trouble getting them picked, and they came on early, and it would be an inducement to get the pickers to come early, they’d pick longer, they’d have early hops to pick. Well, that was a damn long drive, a good hour’s drive up there. And you drove down into this valley and you drove down and pretty soon this neck kind of opened up and here was this hop yard. It was in the spring of the year, and Ervin had loaded the tractor up. At that time, we had that one Case tractor, and neither Orval nor Harvey had a tractor. So there was Orval’s hops, he had 40 acres up there [on Finlay Road, the old Golf Course Road], and Harvey had 20 [on Evergreen Road]. And we had the home place, which was Dad’s 27 and Ervin’s 14 or 15, and that one tractor had to do all that work.

Well, Ervin loaded the tractor up and took it up to Jordan Valley. But it was too wet up there, he couldn’t work. And the weeds were coming up in our hop yards, and they needed working in the worst way. Our ground was ready, and it could be worked. And I remember this one morning, Dad was at the table and Mom was washing dishes, we’d just gotten through eating breakfast. And Dad asked Ervin, “When are you going to get that tractor home, we need to work this ground around here?” And Ervin said, “Well, it’s going to be another two or three days, at least, before we can get in.” And they bantered back and forth, and Mom didn’t say a word. And pretty soon she turned around and said, “I want that goddamned tractor home tomorrow morning, and it had better be home!” And Dad and Ervin both started to say something, and she slammed her fist down and said, “That godddamned tractor is coming home. Now!” Well, I’ll tell you he got in the truck and that tractor came home that day, and the next day it went to work in our hop yard. I was probably 15, 16, so I suppose it was the late ’30s somewhere. Ervin could shit on Dad, and everything would be forgiven. Mom went to a point with him, she loved all of her children very dearly, and she didn’t want to do anything to upset or hurt the kids, but only up to a point. But when it got to that point… and that’s one of only two or three times that I can remember her getting hostile or up in the air or anything, but she had just had enough. And that’s probably the only time I ever heard her say ‘goddamn’. She’d say ‘damn’, or if she was really P.O.’d she’d say ‘shit!’. She swore very little. Something I remember her saying about children was, “When they’re small, they step on your toes. When they’re big, they step on your heart.”

We never played any games at home to speak of, other than Pinochle once in a while, or a little checkers. That was about the only game Dad and I played, was checkers. Mom, she was either quilting or making a quilt, or of an evening she was sewing, that’s all she did was sew in her idle and spare time. She never knitted, but she crocheted. She’d make dish towels or pillow cases and crochet a trimming around them. Make them out of flour sacks. Bleach the printing out of the flour sacks, and bind the edges of them, and crochet a fringe around the edge of them. She’d buy a pattern, and use a hot iron to make the imprint on them, then embroider those. She never made us clothes, but she mended clothes all the times. She made herself clothes, but never anyone else. But mend clothes, my god, that women would patch and patch and patch. If your pants got so bad that there was no more use in them, then she’d cut the good parts out and use them to mend other pants.

Dad died in ’53 [from a heart attack, but he was also close to dying from prostate cancer that had matastasized], and Mom couldn’t hardly handle that. Then Ervin getting shot… she was a basket case, absolutely a basket case. She was a wonderful woman, my mother was. Never had much education. Matter of fact, the education she got, she got from her kids. She never finished the third grade in school, in Indiana, she had to go to work. So, her education was what us kids went to school and come home and taught her, that was her education as far as writing and arithmetic and this kind of thing. As far as cooking, the woman was a wonderful cook, a wonderful cook. When we got married, it used to make Wilma so mad. She’d go down and ask, “What did you put in it?” and Mom would answer,“Oh, just a little of this and a little of that.” “Well, how much?” “Oh, just a little of this, a little of that.”

Summer 1955 – Sarah Kaser and her grandson Everett Kaser (age 2 1/2). This was the last picture taken of her, about two weeks before a devastating series of strokes.

After Dad died, we had to take her down to the bank and teach her how to write a check. Mom had beautiful handwriting. She wrote very slow, but she had a beautiful hand. But she didn’t know how to fill out a check. Because dad filled out all of the checks up until about the time I got to be 16 or 17, and then I started doing the bookwork for him. I kept track of the people’s hours, and I’d write the checks out, and Dad would sign them. At 25 cents an hour, that’s what he paid for hop yard help at that time. So if you worked a full six days, you got $12, at that time a pretty damn good pay check, $12, bought a lot of groceries. Bread was 10 cents a loaf, sometimes on sale 8 or 9 cents a loaf. We never deducted Social Security, the only thing we withheld was Worker’s Compensation. Social Security was non-existent at the time, as far as we were concerned on the farm. I can remember having that payroll book with everybody’s name in it, and how many days they worked, and how many hours they worked, and Saturday was payday. I’d go in about 3:00 o’clock and figure out what they had coming for the week, and when they came in at 5:00 o’clock, off work, I handed them the checks and dad would sign them. Dad died in August 1953.

Sometime after Dad’s hop yard was pulled out, the place was sewed to grain. I know that’s what Ervin and Harvey got into a fight about, because they had somebody come harvest Mom’s grain, and Ervin took Mom’s grain down to the Wilco… well, it was Valley Co-op at that time, and the elevator was still there, and he put her grain in his name. That’s what he and Harvey got into it about, and that’s when Harvey poked him. Then Harvey went down and straightened it out and put that grain back in her name. That would have had to have been about ’53 or ’54.

Ervin never paid much attention to Phyllis, Mary’s daughter from a previous marriage. So as far as him wanting to have kids, he didn’t, other than teasing them once in a while, that’s all he done with kids is tease the hell out of them. I’m trying to think back to when Ervin and Mary were married, and Phyllis was just a little girl then, somewhere between 4 and 6 years old. They would come to family get-togethers once in a while, but thinking back on these family gatherings, Ervin never mixed in with the rest of us so much, he was more or less back by himself. So far as playing cards, that’s pretty much all we did when we got together was play cards, he just didn’t. Mary got along pretty well, I liked Mary, I never had any problems with Mary, but she stopped socializing with the family after Ervin was shot.

I wasn’t proud of Ervin as a brother, not one damn bit. I give him credit for what he could do. He was a hell of a mechanic, and he had a lot of ideas of making things, machinery. If he was in today’s day and age, he’d probably command a pretty damn good job. Because he was smart, in that sense. There wasn’t much of anything that the guy couldn’t make. Mechanically, he was brilliant, but as a person he was a plain horse’s ass. He caused the folks more problems, they spent more money on him than all the rest of us put together. Ervin didn’t really get along with anybody. Ervin was a womanizer. He was a bastard and a prick to work for, he was hot-headed. I don’t know how many times he left home and left the folks holding the bag to pay the mortgage on the farm that they bought for him. Even when they came to family gatherings and Ervin was married to Mary, I can remember him sitting on the… At home, the only heat they had was a furnace in the basement, and it had one big register about three feet square, in the living room. And I can still see him sitting there on his haunches, with his face in his hands like this. He just didn’t communicate with us. Usually when we got together, we played pinochle, Harvey and Orval and Melvin and I. We just threw cards out and the first two of whatever was partners, we had no definite partners. And we played a LOT of pinochle when we got together, and I can’t remember Ervin ever playing. Dad played with us sometimes, but Ervin never played, never. He was not a card player, he wasn’t into socializing, he was a womanizer. He’d screw anything that would spread her legs for him. That’s the way he was.

Cloreta, Melvin Kaser’s wife, said:

None of them [Ervin’s brothers and sister] got along with Ervin. You know, sometimes a lot of people think about other people and think they’re just great, and then all of a sudden something happens, like Ervin being killed, and that was so uncalled for, where jealousy takes hold of you. But I don’t think too many of the boys got along with Ervin. After Ervin was killed, it seemed like no one could get along very well with Harvey. Then, of course, Ervin being shot, that just mixed the whole family up. Melvin and I, we thought it had something to do with Harvey. Of course, it had to do with Harvey because it went through Edith and into Ethel. But I got along with all of them. But I know Melvin and Ervin didn’t get along. They were running the hop yard for a while, the two of them together. When Steven was born in August, it was so hot, and he was such a big baby. I worked on the hop machine at night, not when I was pregnant. Melvin worked nights, too, but he was at the hospital with me, and Ervin told him, “I wish t’hell you’d do your foolin’ around so it didn’t fall at hop picking time!” And he wasn’t even a father, I don’t know why he’d say that. Melvin said, “I just turned my back on him.”

Edith, Harvey Kaser’s wife, said:

Harvey got along okay with his family. Of course, Ervin was always a little hard to get along with, but I think just as good as any family perhaps. It always appeared to me that with Ervin, his folks were always kind of afraid of him, afraid he’d do something that would shame them, not physically afraid, you know. I think he had a hold on them somehow that the other boys didn’t have. But then, he had a beautiful personality when he wanted to turn it on, a wonderful personality. Then, when he didn’t want to, not that he was mean, just that he was unpleasant to be around. I think in all families, if they stayed at home until they got married, a lot of them wouldn’t get along either. With all that family and only one bathroom, well, you know, there was no dilly-dallying around the bathroom. Lucky they only had one girl, I guess. But Veneta was a hard-working woman, helped her mother terrifically. She always felt that the boys were favored over her. Veneta always thought that, but I don’t know that they were. But in terms of the housework, with that many boys, that was a big burden for Veneta to help to do all that, but somebody had to help, and since Veneta was there, she had to help.

Bluffton, Indiana – Mary Klopfenstein Frauhiger and children (clockwise from front-left) John, Jake, Irma, Sarah and Dell. Around 1890, give or take a couple of years.

But Harvey’s mother [Sarah Frauhiger Kaser] had a very hard childhood. Her father died when she was very small, and her grandfather Klopfenstein took her in, and she was living with and working for this Klopfenstein family which owned a distillery. She only got to the third grade in school. She worked out with the hogs shoveling manure, and she worked in the house. After she got married, she never left the house unless the dishes were done, never. Because she remembered, when she was coming home from school, at the distillery they hired a lot of hired men, and they fed them in the house, and they left all the dishes for her to do, and I don’t suppose they had running water neither. So, when she came home from school, here was all of these dishes to be done, and she made up her mind that when she had her own house, that she would never go out of that house and leave dirty dishes for somebody else to wash, and I think it might have been very rare that she ever did. The mash from the distillery, they fed to the pigs, and she said the pigs were always drunk.

Emma Kaser’s wedding day, all are cousins except the Kaufman brothers.

Front (left to right): Martha Krug, Nova Baumgartner, Ervin Kaser, Rita Kaser,

Edna Klopfenstein

Back (left to right): George Kaufman, Alvin Krug, Leona Baumgartner, Ben

Kaufman, Emma Kaser, Veneta Kaser, Minnie Krug

Lynn Kuenzi, first cousin to Ervin, and youngest son of Ervin’s aunt Emma Kaser Kuenzi, said:

All I can remember, growing up, is that Mom [Emma Kuenzi] had a tremendous respect for Ervin, and she loved him. But I remember her saying how he never would smoke in front of her, and she took that as a sign of respect. My brother Glen has told me over and over that, without Ervin, his hop operation would not have been as successful. Ervin used to come up and check the hops for him, to see when he needed to spray and that type of thing. Glen had three or four acres of hops, pretty insignificant, but Ervin took time to do that. So, why Mom was so connected with Ervin, I really don’t know, other than he was one of the older nephews, only about six years younger than her. Mom knew all about his life, but I don’t remember Mom ever going there, about his life. As far as she was concerned, he was her nephew and he respected her, and he was always respectful of her. But I remember that morning, good grief, Mom was a basket case. We kids were just about to leave for school, to walk to school, and that was hard on Mom, really hard on her. But I don’t remember personally Ervin coming to our house, so obviously he must have stopped by in prior years more, when she and Dad were first married. It wouldn’t have been at reunions. Maybe the times she went over to visit Uncle Fred, if Ervin would happen to come over, but she never did say that. I think he just stopped at our place and would visit with her, and maybe he had some mutual respect for her, some memory. But I always remembered that Mom thought so highly of him, because he respected her enough that he wouldn’t smoke in front of her. He was, not a recluse, but he was a little bit removed.

Lee [Lynn’s second-oldest brother] had the hops first, and then when Glen took over, they put them up for machine picking. And, you know what, I’m quite sure that Ervin picked them. In our family, he was looked at with a real positive image. I’m sure that Mom knew his problems of life. You have to remember that Mom’s family couldn’t do too much bad in her eyes, she had a real love for the Kaser family, and it was very easy for her to forgive any problems. You know about Veneta, she could be outspoken, but to Mom she was like a sister, because they were almost the same age. So, Veneta and Ervin, and Edna, those were like sisters to Mom, because they were so close in age, so Mom had a tremendous love for those kids. Many of Mom’s siblings were much older than her and gone. Mom never really connected with Lizzie until later years when she came back to Silverton. Aunt Bertha was gone, and Aunt Lydia was in Portland, so these nieces and nephews were pretty vital.

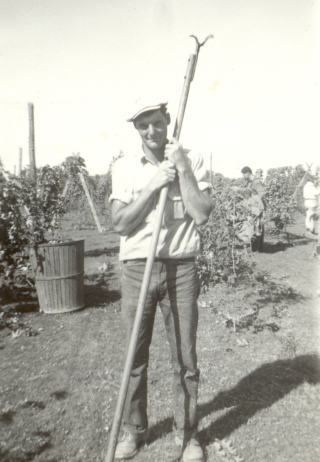

It was definitely a different time back then, and while people are basically the same in every time and place, life’s experiences change drastically through the years as culture and technologies change. Life on a farm 75 to 100 years ago was unending work, hard work, mostly manual labor. That was Ervin’s life.