This chapter will come in bits and pieces, and not necessarily in the proper order. It’s going to be way longer than what would be good for a blog post, so I’ll break it up into pieces that seem to be somewhat cohesive. It’s far from all written, so you’ll be getting “first draft” material. The purpose of this chapter is to show what Ervin’s life was like, what his family life was like, essentially the ‘environment’ in which he lived his life.

Blogically Yours,

Everett

—

Ervin Kaser’s parents, Fred Kaser Jr. and Sarah Frauhiger, were married February 7, 1905. Ervin Oren Kaser was born on their farm November 16, 1905. A daughter, Velma, was born November 17, 1906, but died three days later. She was followed by a daughter Veneta (1907) and sons Orval (1911), Harvey (1913), Melvin (1916) and Calvin (1922). Calvin was a “late in life surprise,” born six years after Melvin when their mother was nearly 42, and I’m the youngest of his four children, so I’m lucky to be here to tell this story. Much of what’s in this chapter comes from my father Calvin, a natural story-teller himself, for which I’m deeply grateful. (According to him, it was only after he was born that she realized, when someone pointed it out, that every one of her children had a first name containing the letter V.)

In August 1914, Fred entered into a contract to purchase a little over 21 acres on the corner of the Silverton-Stayton Highway (today called the Cascade Highway) and Evergreen Road, and the property was paid off and the deed transfer recorded March 24, 1920. They built a new house on the property in 1921 (shown here), which is where Calvin was born. Fred sold to the local school district about an acre on the corner of his farm, which is where the Evergreen School stands today (additional land was acquired by the school district in following years to expand the school grounds). Fred and Sarah lived on this farm for the rest of their lives. They bought another 7 acres on the back-end (west side) of their farm, recorded in 1942, although the private purchase probably happened much earlier.

Fred was a hop farmer, as his father had been before him. Fred grew up farming hops, and that was pretty much all he farmed his entire life, other than the usual chickens, pigs, cows and horses necessary to life on a farm in those days. All of the boys helped run the farm with their father. Fred told the boys that if they worked on the farm without wages, then when they turned 21, he would either give them $1000 to spend however they wanted, or he’d help them buy their own farms. At some point in the late 1920s or early 1930s, Fred bought 20 acres immediately west of their farm (behind it on Evergreen Road), and those 20 acres would eventually be transferred to Ervin and Mary Kaser on November 24, 1941. Ervin lived in an old run-down house on that place off and on throughout the 1930s.

The family farm wasn’t large. They usually had two or three cows for milk, cream and meat, along with hogs and chickens. They did all their own butchering, made sausages from pig intestines and beef and pork meat, made sauerkraut from cabbage they grew, and besides large sacks of flour and sugar, grew most of what they ate. At one time the farm had been covered in large fir trees which had already been logged off by the time Fred and Sarah bought the property, covered in tree stumps. Fred cleared the land using dynamite, ax, shovel and horses. The last stumps, on the lower part of the property, were cleared when Calvin was 4-5 years old, around 1926. Fred used horses to drag the stumps into piles for burning.

The family in 1930 (left to right)

Orval, Fred, Harvey, Veneta (back), Calvin (front), Melvin, Sarah, Ervin

The following is Calvin’s description of working in the hop yard, told to me verbally, and I’ve cleaned it up some for readability, but otherwise the words are his:

I started working full time on the farm when I was 13, right out of grade school that June, and went right to work in the hop yard, and never let up. Anytime it was nice, you were working in the hop yard, or you were making poles or hop stakes, that was quite a job. There were 100 hills to a row, and I forget how many rows there were, but you had to have a stake for every hill, maybe 20,000 of those every winter. You pounded the stake in by the hill, and then tied the string from the wire down to that stake, and they had to be replaced every year.

You’d go out and get a fir tree that looked like it would split pretty good, and cut it into 16 inch lengths. I sometimes made them with a fro, a piece of iron about a foot long by 2 inches wide, with a sharp edge on it, and it has a ring on one end with a handle. And then you’d put the fro on there and hit it with a wooden mallet and split the wood off. I didn’t use the fro much, I used an ax. And you just took a block of wood and cut it down into chunks the width of a double-bladed ax, and you’d slab these off into ½ or ¾ inch slabs, and when you got them cut off into slabs, then you turn the slabs around and hit them the other way, and the stakes would fall down, because you were always sitting at a chopping block. You had a box made there, and that box about level-full would be about 200 stakes. We didn’t count them, but we counted the first one, just to know about how full to fill this box. Then you just lay a piece of binder twine down in the bottom of this box, and then lay these stakes down in there nice and straight. When it was full enough, you tied the bundle off and stacked them up.

Then in the spring, you’d put a bundle of stakes in a bucket and take them out and drive them in the ground by each hop hill after the hops had been cleaned out and hoed, one stake by each hill. Very rarely would a stake last two years, drive them in in the spring and by the next year they’d be rotted and broken off. After the hops were picked, you’d go out with a butcher knife in your hand, and you’d grab this vine and cut it off about this high off the ground, and then you’d drag it along as far as you could hold a big hand full, and then drop them on the ground, and that was how a lot of these stakes got broke off. It was nothing but back-breaking work, working in the hop yard, everything you did was stooping over, everything but tying the strings up on the wires. As soon as the vine got up to the wire, you went through and ran your hand down over the bottom 3 feet of the vine and stripped all the leaves and the arms off, because it didn’t produce much hops down there, and that way the plant didn’t waste energy on those leaves, and they could get wind-whipped and tear the plant down.

Usually, in January or February, we’d get two to four weeks of cold weather. At night it would freeze, and then during the day it would warm up and you’d be out there working in your shirt sleeves and getting a sweat up. And at night, it would get cold and freeze up again. And, when we were making hop poles and that kind of stuff, when the ground was frozen in the morning, that’s when we’d go and load up the hop poles we’d made the day before and haul them out, because by ten o’clock, the ground would be starting to thaw, and the damn truck wouldn’t go, you’d slip in the mud.

Usually the trees we made into hop poles were 6-8 inches in diameter. Of course, they went up there a long ways, and we’d usually get two 12 foot poles out of one tree. At that time, there was still a lot of timber around here, and the trees would come up thicker than the hair on a dog, and hardly any limbs on them, and rather than cut them down with a saw, I’d cut them down with an axe. I got pretty damn good with an axe, it didn’t take too many blows with an axe to knock a tree over. The anchor poles, that’s a different story, they’d have a 10-14 inch top on them. We used a small post for the center posts, and a lot of times we’d cut a 12-foot pole and split it with wedges.

I think of all the timber we sawed up back then, for wood and for poles. My god, I can remember some of them big old growth firs we’d fall down, use them for furnace wood. Some of them damn things would be 4 and 5 foot through. I can remember Ervin bought that drag saw, first time I’d ever seen one, and we thought that was the cat’s meow. Most of them old growth were full of pitch, and you’d try to do it with an old bull fiddle, and the pitch would get on there, and you’d just pull on it. And you had a bottle there with oil and kerosene mixed together and you’d pour that on there. And of course, some of them had so much pitch in them it would just run out of there, my god, you wouldn’t believe how the pitch would run out of there. With the drag saw, you just set it up there and when it started hitting the pitch, you’d just pour the oil and kerosene on. But the grain would be so fine, that you’d stand up there on top of those 4 foot wide blocks and drive two wedges in opposite each other and split it, get it broken in half, 16 inch thick blocks, and most of the time you could take an axe and just peel pieces off all the way around. Oh we made hundreds of cords out of prime timber. Of course, at the time, they wouldn’t have taken those that were full of pitch. And some of the time, the tree might be dying, but today, even if the heart was goady, as we called it, dry rot, there’d be that much meat around the outside of it, and that’s what we used to make our hop stakes out of.

But the poles, 14 inches was about the biggest. You’d set them in the ground about 3 feet. And we always peeled them, take three strips, peel the bark. In the summer time then, when it started to dry out and the top of this 9 foot that was out of the ground would start to get hard, and with this wire around the top choking them, and in the winter after 2-3 years with the rain coming down, it would rot the top and the top would come off, and we’d have to replace them. After they rotted off at the ground, we’d saw them up and use them as wood for the hop dryer.

But you didn’t want the post too big, because you had an eight foot row, eight foot apart. Now, if you put a 12 inch post in, you’re down to a seven foot row to get the machinery in there to work the ground. So that’s why we were so particular when people were hoeing the hops, to keep shoots from coming up further out into the row, or pretty soon you couldn’t get the machinery down through there. There’d be a few hills would die out each year, but usually it was from injury, and most of the injury was from people hoeing hops. Because as this vine came up, after you picked the hops, you cut the vine down off of the wire. And usually right after hop picking, before the sap got out of the vine and they got too dry, we’d go along with a corn knife, and in later years something like a butcher knife, same knife we used for suckering the hops, cutting the suckers off, we’d go along and grab this vine and cut it off at the ground, and leave a stub. And we’d hold these vines until you got a hand full and then you’d drop them. And when you got through, you’d have these rows of piles, and you’d roll them all together and then burn them.

In the spring when the guys were hoeing, it was real easy… you’d have a stick about that wide, where your hop hill was… and you’d plow the hops, take a horse with a 10” plow… and I’d go through with the tractor and have two #12 bottom-plows on it, and plow the ground to the center of the row, go down and come back, plow the ground away from these rows. And then Alvis [Alvis Brunner, first cousin to Calvin’s father Fred] would take the horse with this small plow and he’d go down and plow the ground away from these hills, as close as he could. And then the hoers would come along, and they’d pull all this ground away from this hill, to get the grass and stuff out of the hill, and also to cut this dead vine off from the year before. We’d tell them to take their knife and cut that off, but if you weren’t watching the bastards, there’d always be one or two that would take his hoe and chop it off. Well, then when you got the ground all cleaned out from the hill, and you’ve got all the new sprouts coming out, you covered the hill back up, and then you couldn’t see. But then the next year, you could tell where this bastard had been hoeing, because that row had a hell of a bunch of dead hills in it. They’d cut down into the crown and it would rot.

So we really had to watch those guys. Of course, we’d tell them maybe twice, and the next time it was, “Go on down to the house and collect your pay!” But they just couldn’t understand why they couldn’t do that. I fired several guys. I was just a kid, and I know they didn’t like it, to take orders from a 16-, 17-year old kid, but Dad couldn’t be out there to look after it, so it was my job to look after it.

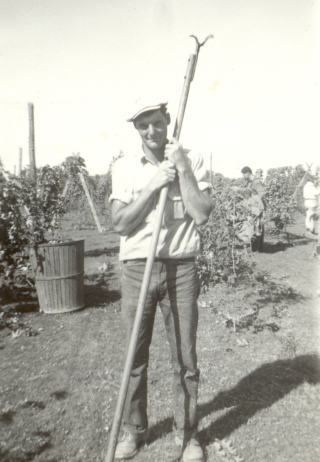

Calvin Kaser, about 18 years old, with pole for lowering and raising the hop wires.

The hop wires have been lowered for the pickers to pick the hops into baskets.

It would be the same way when they’d sucker. When you trained these vines up, you’d usually take four vines, you’d have two strings coming down and you’d train two vines up each string from each hill. Then you had a whole bunch of other vines around here, and you didn’t want that, it would take strength from the plant. So now you’d cut these off. Well, a lot of them, you had these four vines coming up and you’d have some around here and you’d take a slice off here and a slice off here. You always took the four strongest vines, and you’d have some coming up in the middle, and what you were supposed to do was get in here and cut these back right to the crown of the plant, but not into the crown. Well, what they’d do is leave a stub about this long. And if you left a stub, with a joint, out would come two more arms immediately, and pretty soon instead of having a clean plant, pretty soon you’d have a bush about this big around. Then, too, you had to be careful with cutting those, or you’d cut off the vine that you had trained up. And there’d be some, you’d get on their ass about leaving these too long, and then they’d just go like this around, and man they were keeping up and moving right along, and after about 20 minutes, you’d look back and here the vine was looking like this. A hop vine, you damage it, and it wilts right away. Then you’d take them back and show them what they were doing, and some of those guys would get pissed off, oh, they’d get pissed off. The women that worked in the hop yard doing the training and the suckering, they were the best. They couldn’t do the hoeing, it was too hard of work, but the women that did the training and suckering, I never had any trouble with them, never did.