Here’s the second of the magazine stories about the murder, this one with a more typically lurid cover. Sex and violence are always successful salesmen…

True Police Cases – October 1955

To Love, To Die!

By Louis Adams

The quickest way for a man to make enemies is to cheat at the game of love.

Once too often the handsome farmer plucked at forbidden fruit – and he died.

Frost was just beginning to sparkle in the fields two miles south of Silverton, Oregon, as Emanuel Kellerhals Jr. burrowed deeper under the comforting warmth of the bedcovers to shut out the chill of the night on February 17,1955.

He was tired from his day’s work and as he closed his eyes he was momentarily annoyed by the slam of a car door. The sound came from the direction of his neighbor’s driveway across the road. “Erv Kaser’s home early tonight,” he muttered to his wife.

Suddenly the tiny bedroom reverberated to the shattering roar of a shot close by. “What was that?” Mrs. Kellerhals asked in alarm, rising to a sitting position. Kellerhals jumped from bed and rushed to the window.

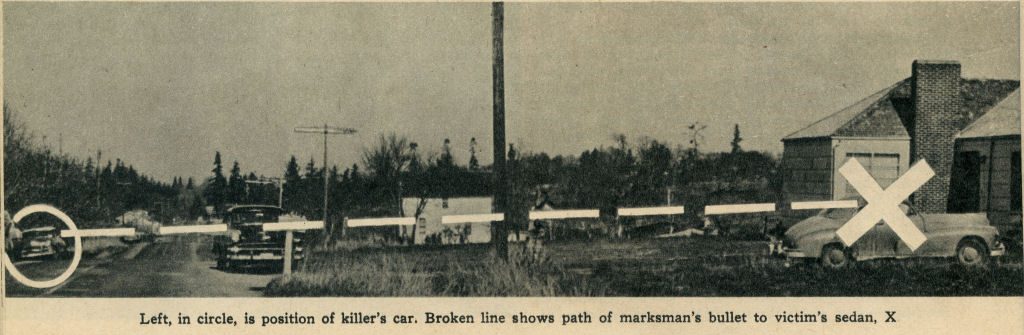

From where he stood, the now thoroughly awakened man could see his neighbor’s sprawling hop farm. Parked in the driveway by the house was Ervin Kaser’s sedan.The dome light was burning. Near the front of his own driveway, Kellerhals observed the shadowy outlines of another car. It appeared to be dark in color.

As he watched, three more shots punctuated the night air and Kellerhals saw vivid flashes corresponding to the sounds. They seemed to come from the strange car in his driveway and, adding force to his visual observations, the motor of the automobile roared into life. The vehicle leaped ahead, and soon its taillights were fading toward Stayton on the Silverton-Stayton highway.

“What’s wrong? What’s going on?” Mrs. Kellerhals inquired anxiously. “Tell me what’s happening out there!”

“I don’t know,” her husband replied, “but it looks as if someone just shot Kaser!”

Kellerhals started to dress, intent on going across the road to see what happened; but then he recalled that there were people better equipped than he to handle such matters. He telephoned Constable Harley DePeal in Silverton.

DePeal contacted Police Chief Raoul Main, and the two men wasted no time in getting to Kaser’s farm. As they pulled to a stop, they noticed the dome light burning in Kaser’s 1949 Plymouth sedan.

The officers rushed up to the car. One glance was all that was required to convince them they needed help beyond that which their own meager departments could give. Constable DePeal called the Marion County sheriff’s office and soon Sheriff Denver Young was on his way from the state capital and county seat at Salem, 13 miles away. As Young left his office he told a deputy to relay the alarm to the Oregon State Police. At the police barracks, Private John Mekkers dispatched State Officer Robert Dunn to the scene.

When the lawmen were assembled, the wheels of a full-scale murder investigation were set in motion.

Ervin Kaser was lying on his right side on the front seat of his car, his feet on the brake pedal and the accelerator. Blood from a wound beneath the victim’s read-and-black plaid jacket was congealing in a pool that had formed on the car seat. The initials E. O. K. on the man’s belt buckle reflected the light from the dome of the car.

“From the looks of things, the poor devil never knew what hit him,” Sheriff Young muttered to Officer Dunn.

The state officer nodded, then suggested that this was a job calling for the talents of Dr. Homer Harris of the state crime laboratory.

“Good idea,” Young agreed. “Get him on his way down here from Portland while I call the coroner.”

Dunn radioed to his dispatcher, with instructions to contact Dr. Harris and have him and a fingerprint technician come down. At the same time, he asked for more help and State Officer Lloyd T. Riegel was dispatched.

Meanwhile, Young, Main and DePeal went across the street to talk to the Kellerhalses.

“It’s all so horrible,” said Mrs. Kellerhals. “Why would anybody do such a thing?”

“That’s what we aim to find out,” Sheriff Young said grimly. “But tell us all you know about it.”

Em Kellerhals described what he had seen and heard when he looked out of his bedroom window.

“What do you know about Kaser?” Young asked when the other finished talking. “Perhaps if we know something about him, it will help establish a motive.”

“Afraid there isn’t much I can tell you,” Kellerhals said. “He was always a pretty good neighbor. Kept to himself though. Maybe someone tried to rob him. He was supposed to be pretty well off.”

“How about visitors? Did he have many?”

“Not many – and what few there were, usually came at night. I think they were men he worked with, but I couldn’t recognize any of them,” Kellerhals declared.

The sheriff asked about the car that had been seen pulling away after the shooting.

“It looked like a Ford. Yes, I’m pretty sure it was a Ford. It sounded like one when it started up,” Kellerhals replied. “It was dark colored, maybe black. It looked like a sedan or coach. I couldn’t tell very well. All there was to see by was starlight.

The officers soon perceived that the Kellerhalses could offer little, if anything, more in the way of information. As they started to leave, Police Chief Main asked if he could use the telephone. He said he hated to do it, but someone had to notify Kaser’s relatives about the murder.

“Oh, I’ve already done that,” Kellerhals interrupted. “I called his brother, Melvin. He should be getting here soon.”

The officers thanked him and started to leave, but as they were on their way out the front door, Sheriff Young turned back and asked, “How do you account for the sequence of sounds, Mr. Kellerhals? The door slamming and then the shots?”

“Gosh, I don’t know,” Kellerhals answerd. “Looks to me as if Kaser maybe got out of his car and started for the house, then something warned him so he got back into his car.”

“That’s about the way it looks to me, too,” Young commented. “He probably intended to drive out of there and never had a chance.”

The coroner and Officer Riegel had arrived by the time the lawmen returned to Kaser’s car. State Officer Dunn quickly filled them in on what he had determined. Kaser’s wallet had not been disturbed and everything seemed in order in the house.

“Doesn’t look as if the motive was robbery,” Dunn concluded. Officer Riegel, meanwhile, had his notebook out, jotting down a physical description of Kaser and making a rough diagram which showed the location of the murder car and the approximate position of the slayer’s automobile before it fled.

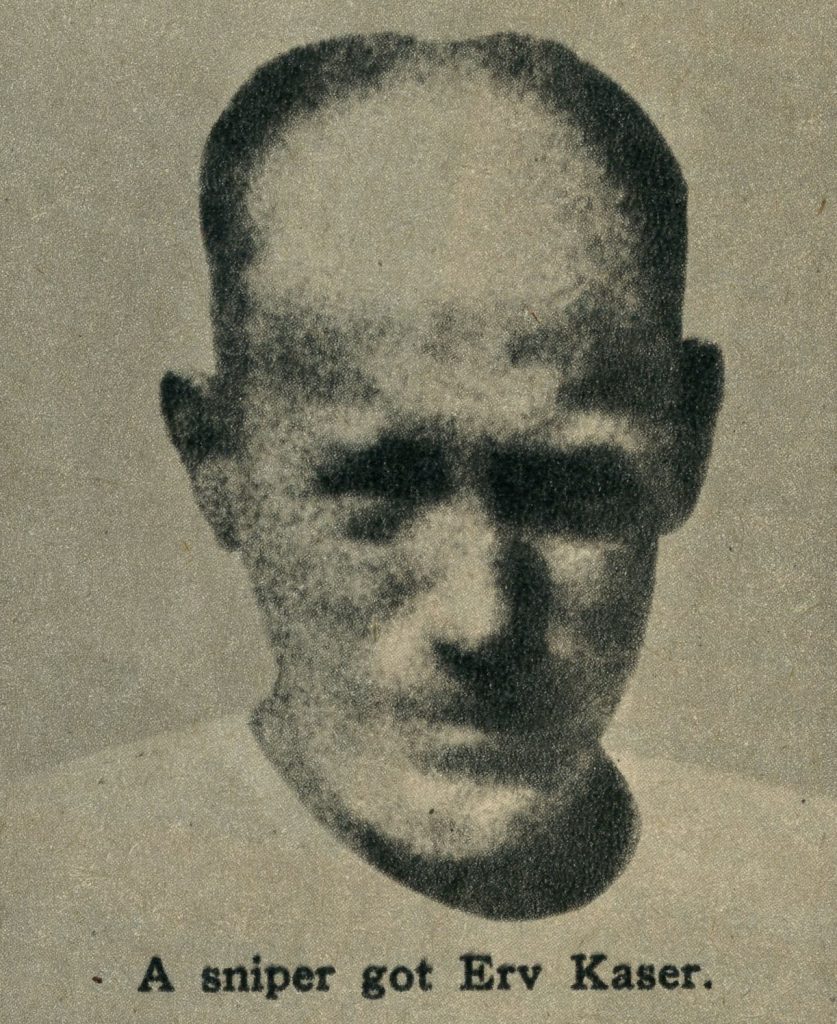

Ervin Kaser, 49, was of medium weight and about five feet ten inches. His brown hair receded in front, but he had been a comparatively handsome man. In addition to the plaid jacket, he wore a gray shirt, dark twill trousers and tan loafers. A gray felt hat was crushed beneath his head.

A sack of groceries in the back seat indicated that the victim had just returned from shopping.

“Have you searched the area where the killer’s car was parked?” asked Young.

“Yes, but we’ll probably have to wait until daylight if we’re going to find anything that might give us a lead,” Dunn replied.

Dr. Harris and Sergeant Ralph Prouty of the state crime laboratory pulled up just then and they immediately got to work. Prouty began shooting pictures of the scene, after which Dr. Harris accompanied the coroner to the morgue where a preliminary autopsy would be performed.

Meanwhile, an examination of Kaser’s sedan revealed that three bullets grouped close together had plowed through the left doorpost; a fourth had gone through an open window and out the windshield. Two of the bullets that had penetrated the doorpost also had gone through the windshield, while the fourth was lodged in Kaser’s body. It struck Kaser in the left shoulder, but did not emerge.

The Kellerhalses had placed the murder car between 50 and 75 yards away from Kaser’s sedan. When Sergeant Prouty learned this he was amazed.

“Whoever did this was a whale of a good shot. Look how closely grouped those shots are on the doorpost,” he said. “Accomplishing that at night is really something.”

Sheriff Young nodded assent. “Of course the killer was helped by the fact that with the dome light on, Kaser made a clear target; but still the sniper is a deadly marksman. We’d better warn the cars that are out hunting him to be careful.” Earlier the sheriff had broadcast a description of the killer’s car and he now issued a warning.

At this point, Constable DePeal introduced Melvin Kaser, brother of the slain man. DePeal stated that Melvin lived just down the road from his brother’s farm and might know something.

Young and Riegel, mindful of the younger brother’s grief over the killing, nevertheless decided to question him immediately rather than wait until later.

“I don’t know what’s behind my brother’s murder,” Melvin Kaser began, “but I can tell you one thing. It definitely was planned. It looks to me as if there must have been other attempts, maybe several times.”

“Why do you think that?” Dunn asked.

“Because the chances are about a million to one for Erv to be parked right where he was shot and for him to have his dome light on to make it easy for the killer.”

“Isn’t there some other reason, too, why you think the murder was planned?” Sheriff Young pressed. “Did your brother have any enemies?”

Melvin Kaser’s brow furrowed in deep thought. He was silent several moments as though weighing something in his mind, then he said:

“Erv was always somewhat of a lone wolf. Sure, he lived next door to me and all of that, but he never told me any of his affairs. He never discussed his friends or where he went. Far as I know, he never had much to do with anybody. Afraid I can’t help you much that way.”

The Silverton police chief, who had been listening, spoke up:

“There’s a lot of talk going around Silverton that Erv was quite a lady’s man. Some say he’s broken up some marriages around here. His wife sued him for divorce not long ago, claiming he was messing around with other women and staying out all night with them. There’s probably several people who won’t be sorry about his death.”

The younger Kaser admitted that he, too, had heard the rumors, but he didn’t know how true they were.

“Well, we’re getting somewhere, at least,” Sheriff Young interrupted. “if we can find out who Ervin Kaser has been dating, we’ll probably find a clue to the killer. This job begins to look like the work of some jealous husband.”

Chief Main nodded agreement. “There’s a carpenter, named Oveross, who lives up the road a way, and I’ve heard that Kaser has been seen with this man’s wife. He might be a good place to start,” the chief suggested.

Sheriff Young thanked Melvin Kaser for his help, conferred briefly with Sergeant Prouty and Officer Riegel, then ordered the carpenter picked up for questioning. “Bring him to my office, and while you’re getting him I’ll talk to District Attorney Kenneth Brown,” the sheriff said.

Casper (Cap) Oveross had lived in the Silverton area all his life. Unlike Kaser, the thin, gum-chewing carpenter was generally well liked by his neighbors. His habitually friendly grin and youthful ways belied his 44 years.

As he entered Sheriff Young’s office and was introduced to District Attorney Brown and State Officer Dunn, Oveross appeared only mildly concerned over being taken from his home in the middle of the night and hustled to the county seat.

The officers wasted little time in obtaining preliminary information from their plaid-shirted subject. He had been born near Rocky Four Corners on Abiqua Creek north of Salem, had graduated from Silverton High School as had his wife, Ethel, and, for 20 years, had lived less than a quarter mile from the murder scene in the Evergreen community.

Did he like Erv Kaser? No. He blamed Kaser for breaking up his marriage. Yes, he had sued his wife for divorce last fall, just a couple of weeks after Mary Kaser filed for divorce from Erv.

Was he glad Kaser was dead? No more so than probably a lot of other husbands in Silverton.

“Where were you when Kaser was killed?” Sheriff Young asked.

“What time did it happen?” Oveross countered.

The sheriff estimated Kaser died about 10:55 p.m.

“I was probably in a tavern over in Silverton about then,” Oveross said, taking a hitch in his blue jeans. “I was in a couple of them during the evening. I hadn’t even got home when your men came to my place.

“Can you fix the exact time when you were in those taverns?” Brown asked.

“Nope, don’t think I can,” the carpenter replied. “Never looked at the clock.”

“You own a gun, don’t you?” Dunn interrupted.

“Not now,” Oveross replied.

The questioning continued several hours, but Casper Oveross stuck to his story concerning his whereabouts during the evening. He steadfastly denied any part in the killing of Kaser.

At midmorning, weary and disgruntled, Young and Brown retired to another room to talk over what had transpired. They agreed that they were getting nowhere; that Oveross should be set free. Certainly he had a motive, but apparently dozens of others in Silverton also had a motive.

“Let him go,” Brown ordered, “but better check on his wife and Kaser’s wife. Maybe they can offer some hint as to who might want Kaser dead.”

“That’s right,” Young agreed. “From what Oveross tells us, Mrs. Kaser divorced Erv because he was chasing around. She just might know of any threats made against her husband.”

“Yes, and if Oveross is right in thinking his wife was going with Kaser, she might be able to suggest a possible suspect,” Brown commented. “Also, maybe Kaser wasn’t romantically interested in Mrs. Oveross but in some other woman.”

The two lawmen returned to the interrogation room and told Oveross he was clear of suspicion; they suggested, however, that he not leave Silverton for the time being.

“It would help us,” said District Attorney Brown, “if you could fix the time more exactly when you were in those taverns.”

“Sure,” the carpenter replied as he took his departure.

With Oveross tentatively cleared, the officers turned their attention toward other suspects. They also decided to check the divorce complaints in the Kaser and Oveross cases.

On August 6, 1954, they learned, Mary Louisa Kaser, wife of the Silverton hop grower, had filed suit. She charged, among other things, that the “defendant does associate with and keep company with another woman or women from time to time.” Unfortunately she didn’t name names.

On August 20, Oveross sued his wife, Ethel, for divorce, alleging that “for the period of several years, the defendant has associated herself with other men, and particularly one other man to such an extent that such association has become public scandal and gossip in the community in which the plaintiff and defendant live.” Neither did he list names, but Oveross had told police he referred to Kaser.

The Kaser divorce trial had been set for March 17, but the murder changed the situation. Defendants in both actions had entered general denials of the allegations in the complaints.

It was evident the women had to be talked to, so interviews were set up.

Mrs. Kaser was contacted at her Salem apartment where she had moved pending settlement of the divorce action. The trim, 40ish blonde told her interrogators that she had no reason to kill Erv. Certainly she was unhappy about his associations with other women, but she had already handled that matter by filing suit for divorce. She indignantly asserted she would never stoop to murder. Before the officers left, Mrs. Kaser had convinced them she knew nothing of real value to aid their search for the killer.

No better luck was encountered in the questioning of the ex-Mrs. Oveross. Obviously overwrought by all that had happened, she nevertheless tried to be cooperative.

The slender divorcée insisted she knew nothing about the killing; she also didn’t think her ex-husband would have done it even in a moment of jealousy. She startled her interrogators by stating that her twin sister was married to Harvey Kaser, a brother of the slain man.

Saturday afternoon, February 19, nearly 40 hours after the killing, District Attorney Brown announced, “This thing is beginning to go around in circles. We’re getting nowhere. Possibly we’ve been concentrating too much on the Kaser-Oveross situation and the real killer is somewhere laughing at us.”

Arrangements were made with state police headquarters to assign Sergeant Wayne Huffman and Officer Lloyd Riegel to work with Sheriff Young and Deputy Amos Shaw until the case was solved, no matter how long it took.

The authorities went into a huddle and sifted through the information already at hand: Kaser was killed at 10:55 p.m., and a dark car had fled from the scene. So far as was known, only Emanuel Kellerhals and his wife had seen that car, and their look at it had been hindered by darkness. Perhaps someone else had seen it under better conditions.

With the help of Silverton officials, a map was drawn which listed every house in a five-mile radius of the Kaser home, particularly those along the Silverton-Stayton highway. Huffman and Riegel were assigned to check each of the houses to determine whether anyone else had seen the murder car. They also decided, for a few nights at least, to stop every car on the highway on the theory that people have pretty definite habits, and some motorist who normally traveled between Silverton and Stayton at that time would have seen something significant.

Sheriff Young and Deputy Shaw, meanwhile, agreed to check other possible suspects. They already had learned that the shot which killed Kaser was fired from a .30-caliber rifle and that the fatal bullet had been either a “lucky” shot or aimed by a perfect marksman.

The rifle slug had punctured the left lung and the arch of the aorta, the great trunk artery from the heart.

“Let’s go over to Silverton and see what we can learn about marksmen,” Young said to his deputy.

Several hours later the two teams met over a cup of coffee to compare progress.

Huffman and Riegel so far had found no one other than the Kellerhalses who had seen the killer’s car, but they had some other interesting information.

“We kept getting the story that Kaser was involved with other men’s wives,” Sergeant Huffman reported. “He also had money problems. He was a hard bargainer with people who worked for him in his hop yard, and there’re stories going around that he didn’t pay some of them.”

“Say, that’s worth checking further,” the sheriff interrupted. “Maybe he fought with one of those workers and the fellow he fought with went for him with a gun.”

“We’re way ahead of you there,” Riegel said. “We’ve been busy compiling a list of former employes and have talked to some of them. Haven’t come up with anything definite yet. However, it should be pointed out that we’re checking stories circulated by people who don’t like Kaser. We’ve heard some good things about him, too, that indicated some of the stories might be distorted.”

Young and Shaw had something to report, too. They had learned that Kaser received a telephone call from eastern Oregon the day before the shooting.

“The phone company is looking that up for me now, and when we’ve got the information, I think someone had better go over to eastern Oregon to see what it’s all about,” the sheriff said. “That call may tie in with the murder.”

The teams separated again, Huffman and Riegel to continue looking up former employes of Kaser; Young and Shaw to make a round of taverns where Oveross said he had been at the time of the murder.

The latter team ran into something at the first tavern they visited. James Lowrie, bartender, said Cap Oveross was an excellent shot – one of the best in the area. He didn’t believe the carpenter had killed Kaser, however –“even though he had good reason” – because Cap was too easy-going to be a murderer. Further, he had been in the tavern the night of the shooting.

“Why do you say he had good reason to kill Kaser?” Shaw asked.

“Because everyone knows Kaser was making a play for Mrs. Oveross. Why, they were together just before the shooting,” Lowrie retorted.

“How do you know that?” Young shot back.

“One of my customers saw them in Kaser’s car driving along the road to Silver Creek Falls State Park,” the bartender replied.

Young and Shaw questioned Lowrie further, learning that he could not definitely fix the time Oveross had been in the tavern. Thanking the bartender for his help, the officers proceeded toward the state park. En route they called for Huffman and Riegel to join them.

Arrived at the popular park grounds, the officers again compared notes and then set about checking nearby houses to determine if anyone had seen the dark sedan that had been at Kaser’s farm. The theory had been suggested that the killer was trailing Kaser on the fatal night. Nothing significant was turned up, so back to Silverton the lawmen went. There questioning of townspeople disclosed that, on the night of the shooting, Mrs. Oveross had been at a lodge meeting, had left for a time, presumably to meet Kaser, and then had returned to the lodge.

“This thing keeps leading right back to the Overosses,” Sergeant Huffman told his fellow officers. “I’ll bet Cap Oveross heard about them meeting Thursday night and trailed Kaser home and killed him.”

“We found out he was a crack shot, too,” Sheriff Young added, “and he’s wrong when he said he had no gun. He’s said to have several. Let’s go talk to him again!”

This time Casper Oveross was not so friendly when police arrived at his home. He grudgingly admitted he had access to some rifles, but said, “You’re mistaken if you think I told you before that I don’t have a gun.”

“Why don’t you tell us about killing Kaser?” Young demanded.

“Listen,” Oveross retorted indignantly, “I’m getting tired of all this monkey business. We went all through it the other night. Now you birds lay off or I’m calling in my attorney.”

“If you’re innocent, then let’s run a lie detector test and prove it once and for all,” Shaw suggested.

“Why should I? It’s just more of the same old malarky. I’m not having any part of it,” the carpenter lashed back.

Basically, the interview produced no more results than the first one, but three rifles Oveross had access to were rounded up for examination by ballistics experts at the crime laboratory.

That night in Salem the officers related their findings of the day to District Attorney Brown.

“It’s getting more complicated all the time. Looks as if a batch of people, not only Oveross, had motives,” Brown commented when they were through.

“You know, I think the key to this whole thing is the murder gun. We’ve got to find it, then we’ll know who the killer really is,” Young said.

“What about the guns you got from Oveross?” Brown asked.

“They’re being checked, but we don’t think any of them is the right one,” Huffman informed the DA.

Before the meeting broke up, it was decided to pick up every .30-caliber weapon in the area for checking by ballistics experts and to drag every stream and pond in case the killer had disposed of the gun.

Sunday, February 20, 1955, saw policemen knocking at every door asking for guns. Residents were surprisingly cooperative and soon a sizable arsenal was on its way to Portland to the crime lab.

Other officers in boats probed all local bodies of water. Dragging operations on two ponds within earshot of the death scene were discontinued when a farmer reported no cars had used the road on Thursday night.

Meanwhile, State Officer Dunn, who had been sent to Madras in eastern Oregon to investigate the Kaser telephone call, returned to report it had no connection with the murder.

Late Sunday, Sheriff Young learned that Oveross had a target range behind his home where he test fired rifles for several of his friends. The sheriff directed that bullets be dug from the range and compared with the one taken from Kaser’s body.

Monday the search for the gun continued, and again on Tuesday morning.

It was late Tuesday afternoon that District Attorney Brown received a call which set him wondering about Paul Hatfield, a friend of Oversoss’ pretty 17-year-old daughter, Colleen. The person who called said the youth knew something.

Young Hatfield was extremely nervous and reticent when police started talking to him. He denied having had anything to do with the murder, but when the questioning swung to Oveross, he became agitated.

“I guess I’d better tell you,” the youth is alleged to have answered. “Cap came to my place a few minutes after the shooting. He said, ‘Kaser’s got three slugs in him and you’ve got to be my alibi. If anybody asks, I was with you last night.’”

Brown jerked his head for Young and Huffman to follow him into another room.

“If what the boy says is true, it looks as if we’ve hit pay dirt,” he said. “Bring Oveross in.”

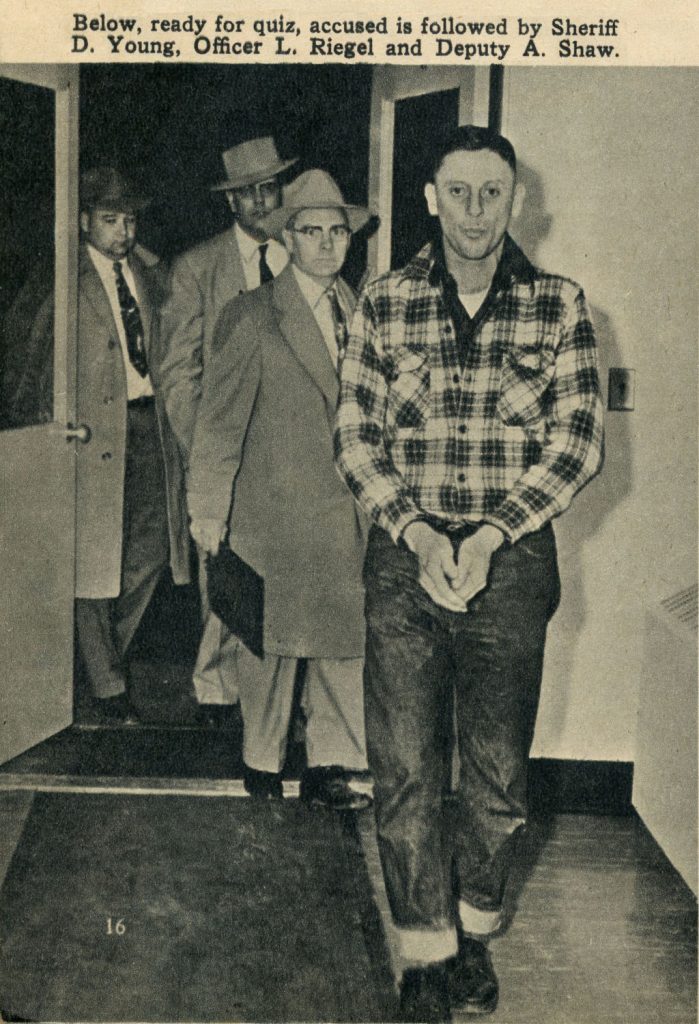

A short time later, armed with a Marion County District Court warrant charging first-degree murder, Deptuy Sheriff Amos Shaw and State Patrolman Lloyd T. Riegel located Casper Oveross at the home of his niece in Silverton.

Oveross indignantly refused to accept his copy of the warrant, but he offered no resistance as he was taken back to Salem and booked into jail. The officers also impounded his 1950 black Ford coach and stored it in a Silverton garage.

All the way to Salem, the rough-clad carpenter refused to answer questions, and when he arrived at the sheriff’s office all he had to say was: “I’m waiting for my attorney.”

It wasn’t long before Defense Attorney Bruce Williams appeared and, after a brief conference with his client, told newspaper reporters there was no evidence whatsoever against Oveross and he would demand the earliest possible preliminary hearing or, failing that, a writ of habeas corpus to free his client from custody.

The next morning, Oveross was arraigned before District Judge Edward O. Stadter Jr., and was granted a March 2, 1955 preliminary hearing. He displayed the same unruffled composure as had marked his behavior almost from the beginning.

That same day, in Marion County Probate Court, Kaser’s widow, Mary Louisa Kaser, was appointed administratrix of her dead husband’s estate. Probable valuation was listed as $10,000 in real property and $1,000 in personal property.

Later, District Attorney Brown called the officers together. “Just because that boy claims Oveross wanted him to serve as an alibi doesn’t mean that Oveross is guilty. Oveross could have heard of the shooting and have known he would be the logical suspect,” the DA said to the gathered men.

When Huffman and Riegel returned to Silverton they found the town buzzing. Some people refused to believe that likable, easygoing Casper Oveross could have had anything to do with the crime. They said they would never believe it until the sheriff’s office proved it beyond a doubt.

Others said that if Oveross did fire the fatal shots, he only did it to scare Kaser – not to kill him. “Why, those shots came so fast that it should prove the rifleman had no intention to hit anyone,” a service station attendant said. “Anybody who deliberately was trying to kill a man under starlight would take a long time between shots.”

Thursday, February 24, 1955, one week after the murder, Dr. Harris and his assistant, Sergeant Prouty, returned to Silverton from Portland to pick up clothing found in Oveross’ car and to examine the interiors of both the Oveross and the Kaser cars.

The next day, District Attorney Brown again conferred with his officers, reviewing all of the evidence that had been collected. There still were some unanswered angles and the murder weapon still had not been discovered, but the DA decided to take the case to the grand jury on the following Monday.

Defense Attorney Williams objected bitterly when he heard the news, then said he would not permit his client to appear before the jury.

A parade of 17 witnesses started going into the grand jury rooms at 9:30 a.m. It included Sheriff Young and Dr. Harris, plus relatives of both Kaser and Oveross. At 4 p.m., the jury made its report to Circuit Judge George R. Duncan.

The jury failed to find the evidence sufficient to support an indictment. Oveross was released, completely exonerated.

District Attorney Brown summoned the police authorities to his office. “We’ve got to start all over again. The murder of Ervin Kaser has got to be solved.”

The Officers reviewed again the facts and rumors they had gathered. Finally Riegel spoke up:

“It still goes back to that missing gun. We’ll have to find it.”

“There’s more to it than that,” the DA said. “Since Oversoss isn’t the guilty party, then it means there’s a killer loose somewhere around here. We still don’t definitely know he’s a jealous husband. He could well be a trigger-happy madman and he may strike again.

“I suggest we call for public help in locating that gun. Maybe the American Legion or the Boy Scouts or some similar group can help search.”

“We’ll keep on looking,” Sheriff Young promised grimly. “We’ll check every hardware store from here to Portland if we have to, and find out who bought 30-30 shells. Then we’ll go to their homes and look at those rifles. We’ll find that rifle and we’ll get the killer!”

The days changed to weeks and the weeks to months, and still the search went on. By the first of May, 1955, more than 100 persons had been talked to. Dozens of ponds were dragged. Dozens of hardware stores were checked. Still no luck.

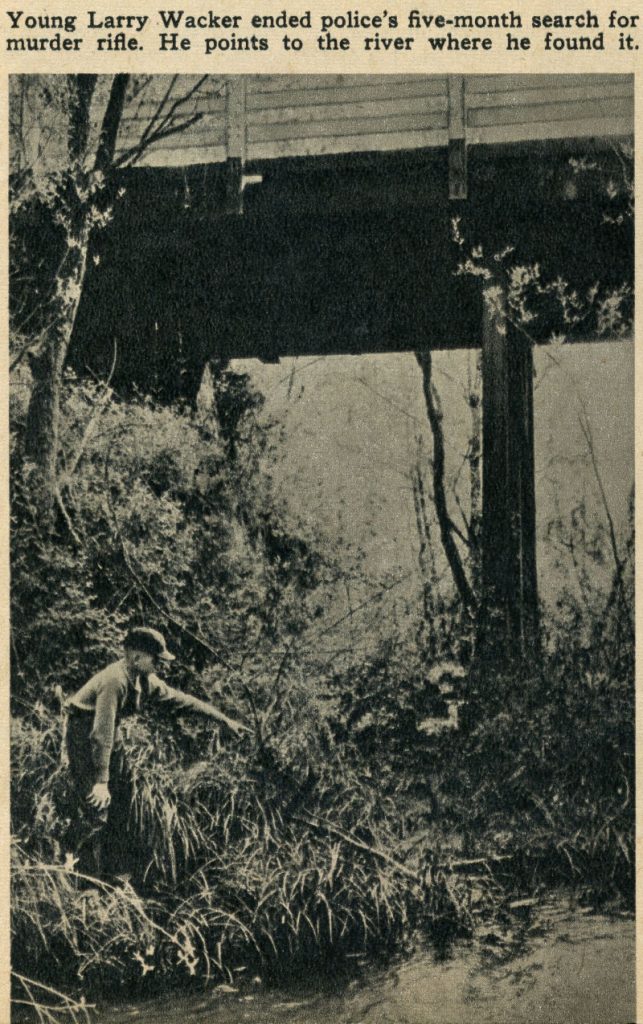

Then Sunday afternoon, May 8, Larry Wacker, 12, of Salem, was playing along the banks of the Pudding River near the small community of Pratum. The spot was five miles by road from Kaser’s farm. Suddenly the boy pulled what he thought was an iron rod from the river. It was a .30-30 rifle.

The boy excitedly turned to his companions, Neil Beutler, 11, and Roger Beutler, 8, and said, “Look what I’ve found!”

The gun was crusted with rust, but young Wacker managed to work the lever. The gun ejected an empty cartridge. A live cartridge still was in the chamber.

The boys rushed to the John Ross home where their parents were visiting. When the fathers examined the gun, they immediately notified the authorities.

Sheriff Young examined the rifle, and was elated. “There is a good possibility this is the murder weapon,” he declared.

The gun and cartridge were immediately sent to the crime laboratory and now the officers redoubled their efforts, this time to determine whether anyone had seen the dark-colored murder car in the vicinity of the Pudding River bridge at any time after the shooting.

On May 12, Sheriff Young received a telephone call from the crime laboratory. When he hung up the phone, he turned to his co-workers and said:

“That’s the death weapon. We’ve got the gun now, the right one. Now all we’ve got to do is prove ownership.”

When District Attorney Brown was informed, he said, “I don’t think we’ll have any trouble showing that Oveross had that gun. I’ll call the grand jury into session again.”

He was even more certain later that afternoon when the sheriff called him to report that a witness had been found who claimed he had seen Oveross near the Pudding River bridge the night of the murder.

On Monday, May 16, 1955, a new grand jury heard the now mountainous pile of evidence in the case. This time police were able to produce a murder weapon. Because of their exhaustive canvass of hardware and sporting-goods stores, they had reason to believe that Oveross had bought one like it; the district attorney was able to present ballistics findings that were not available for the first grand jury.

The jury did not take long to indict Cap Oveross with first-degree murder.

Then the officers got a shock. Oveross was not in Silverton. He reportedly was somewhere in northern California visiting relatives. Defense Attorney Williams, however, was unconcerned. He told police he was certain his client would return home as soon as he heard of the indictment.

The attorney was correct. A few days later, at Fairbanks, Alaska, where he had been working on a construction job, Oveross walked into the office of the U. S. Attorney and identified himself. He had just learned of the indictment and was anxious to prove his innocence. Sheriff Young and Sergeant Huffman soon went to Alaska to accompany the carpenter back to Silverton.

Oveross still maintained the same calm as before when he was returned to Salem. He still declares he is innocent and is ready to clear himself of the murder charge in court.

NOTE: The names James Lowrie and Paul Hatfield, as used in the foregoing account are fictitious to protect the identities of the persons innocently involved in the investigation.

NOTE: Obviously, Paul Hatfield was really Dan Gilham.

And that’s it for the second magazine. Next up, the third magazine, Real Detective.

Blogically yours,

Everett