…And here’s the final magazine story about the murder. As the author says near the beginning of the article, “It’s been nearly six weeks…” So, this article was written around the end of March, before the rifle was found and before Cap Oveross was arrested the second time and indicted.

Real Detective – August 1955

WHODUNIT?

By Steve Clay

Silverton, Oregon has 3164 residents and one corpse. But if you ask who the killer was, Silverton’ll shrug its shoulders.

SILVERTON’S LOOKING for a murderer.

And it doesn’t look like it’ll find him.

It’s been nearly six weeks since the cops found 49-year-old Erv Kaser dead in his own driveway, slumped against the dashboard of his bullet-riddled Plymouth with a.30-caliber slug lodged near his heart.

It’s been five weeks since they tried to pin the rap on a local carpenter.

And it’s been only a little less than that since they admitted they were stymied.

One cop says they’re caught in an endless circle. Everything they check seems to run back to something they’ve checked before.

District Attorney Ken Brown says the town’s full of rumors. There are plenty of things the cops could investigate.

A newspaper reporter in nearby Salem, the state capital, says something could break any time. It always can.

But most of the cops aren’t saying much of anything. Sheriff Denver Young and the state troopers just tell everyone they’re continuing their investigation and have lots of evidence. They’re keeping it secret until the right moment.

They thought they had lots of evidence five weeks ago, too, a few days after the murder. They thought they had the killer.

They must have kept a lot of their evidence secret then, too, because a grand jury didn’t agree with them. And now all Silverton’s wondering who Erv Kaser’s killer really is.

And it looks like it’ll keep on wondering, unless and until a shadowy, sharpshooting killer comes out of the tall, green Oregon firs to kill again. Because he’s still free and, the way things are going, he may stay free forever….

It was Em Kellerhals who saw Erv Kaser die. He was lying in bed the windblown night of February 17, when he heard Erv pull into the driveway of his pleasant-looking white frame house across the way. He looked at the hands on his luminous watch and noticed it was a few minutes to eleven.

As he remembers it now, he heard Erv slam the door to his car and, within a matter of three seconds, the quick whine of a single bullet. By the time he’d gotten out of bed and to his front window, he found he was just in time to see three quick white flashes and watch the slugs crunch into the windshield of Erv’s car.

They came from a dark-looking sedan parked a few feet from Em’s own driveway and about 75 feet from Erv’s car. As soon as the fourth bullet had been fired, the sedan sped off down the black-topped road toward Stayton, hurtling forward into the wind. Em said it sounded like a Ford.

Silverton Constable Harley DePeal was the first cop to get to the murder scene. He was followed by Sheriff Denver Young and other officers from the Marion County sheriff’s office. Then came the state police.

What they found out about Erv Kaser in the next 24 hours was enough to show that several people might have wanted to kill him. Em Kellerhals said Erv was a good neighbor, but a lot of people around Silverton didn’t like him. They said he’d caused a lot of family arguments and broken up several marriages around the countryside.

And Erv Kaser had been in the process of getting a divorce himself. In August, 1954, his wife, Mary, had filed suit against him, charging him with associating with other women, staying out all night and striking and beating her. When she filed it, she moved into an apartment in Salem, 15 miles away.

Erv hadn’t wasted any time. He’d turned right around and filed suit against her. He denied all her charges and thought up some of his own. He said he’d be glad when the case came to trial March 17.

The cops talked with Mary Kaser about the victim, but they were more interested in what Erv’s younger brother, Mel Kaser, had to say about him. He described Erv as a lone wolf, said he always concealed his affairs, his friends and his goings and comings.

And Mel also said he and his friends thought Erv’s death had been carefully planned. And he didn’t think February 17 was the first time that Erv’s killer had tried to do him in. He said it was unusual for Erv to park just where he did and that it was a million-to-one shot that the killing had gone off just the way it had. He figured the murderer must have known Erv and his habits pretty well.

It was as plain to the cops as a big piece of lumber that Erv Kaser had been a trouble maker and a lone wolf, a man whom few people knew well and some people thought they knew too damn well, a man whom many residents might have liked to see out of the way.

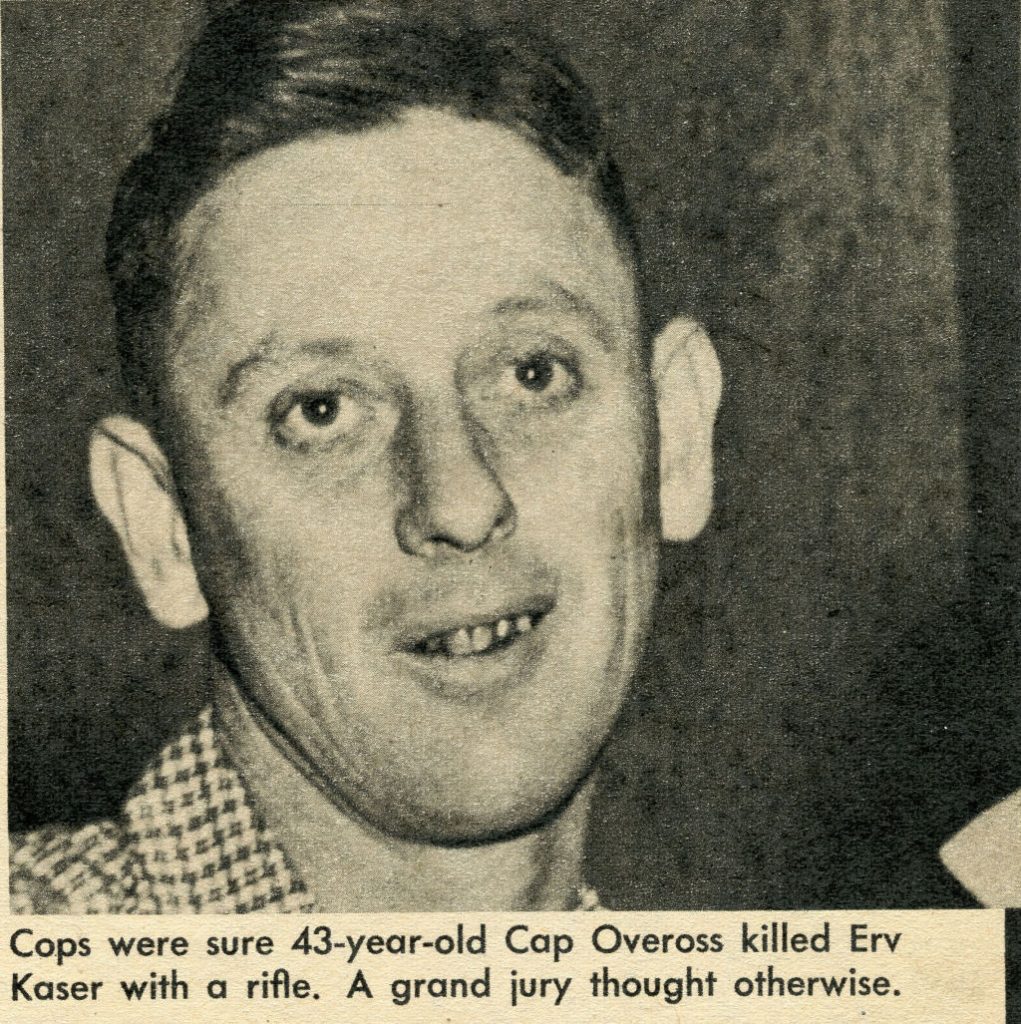

They thought there was one man in particular, however, who might have liked to kill Erv Kaser. His name was Cap Oveross. His age was 44. His occupation, carpentry.

Like Erv, Cap had been separated from his wife. Two weeks after Mary Kaser filed suit against Erv, Cap had asked his wife for a divorce. He’d gotten it in October.

And, just as Mary Kaser had accused Erv of associating with other women, Cap Oveross had accused his wife of associating with other men and one in particular. He didn’t name him in the divorce suit, but he told plenty of people around Silverton who he considered responsible for the breakup of his marriage. A man named Erv Kaser.

LIVED NEAR KASER

There were a couple of other things about Cap Oveross that interested Denver Young and the state troopers. He’d lived for 20 years only one half mile east of Erv Kaser. He had a car, a dark 1950 Ford tudor sedan. And he was a crack shot with a rifle and had had a target range on the little farm where he’d lived before his divorce.

Within 24 hours of the death of Erv Kaser, police had long and extensive talks with Cap Oveross. Cap was nonchalant enough. He just told them he’d spent Thursday evening, February 17, in two taverns and thought he’d been in one of them both before and during the approximate hour of the killing.

The cops didn’t like his story. They said it was too hazy.

And they didn’t like the facts that he had a motive, had a Ford and had a gun.

But they let him go because they didn’t have enough evidence to hold him. And they talked with even more people who might have wanted to kill Erv Kaser and started investigating the murder scene.

Saturday, both sheriff’s deputies and state troopers scoured the entire Silverton neighborhood for the murder weapon. Streams were dragged. Abandoned wells were searched. Woods were probed.

Sunday, two ponds were dragged, one within a half mile of the victim’s home, three miles south of Silverton. No weapon was found.

But three rifles to which Cap Oveross had access were impounded and sent to the state police crime laboratory for inspection. Cap’s own hunting rifle was not found.

His car was found though, and they impounded it, too, and sent it to the crime laboratory for inspection. Because one thing seemed sure – the four shots that had slammed into Erv Kaser’s car had been fired from inside the killer’s car. Em Kellerhals said it had looked like that to him, and he said the car had started up immediately after the last quick, white flash.

CONTINUED INVESTIGATION

Monday and Tuesday, the cops continued their investigation, comparing bullets found at the murder scene with slugs in the possession of various suspects, working quietly and secretly, telling as little to the newspaper reporters as they could. But, by Tuesday afternoon, word had gotten around Silverton that Denver Young and the state troopers had made little progress.

The word was wrong. Because, early Tuesday evening, Cap Oveross was arrested in his niece’s home in Silverton, and Cap didn’t like it one bit. He refused to accept the arrest warrant.

The cops made him accept it though and took him to state police headquarters in Salem, but that didn’t change Cap’s attitude at all. All he would say was that his name was spelled with a ‘C’ instead of a ‘K,’ as the warrant had it, and that he wanted his lawyer, Bruce Williams.

When the cops tried to find out more, the lean, laconic carpenter scratched at his bright plaid shirt, hitched at the belt on his blue jeans, looked down at his rolled-up cuffs – and turned toward the wall.

When his neighbors heard about it, most of them didn’t blame him. The news of what had happened started coming over the telephone wires strung through the big Oregon firs within an hour of his arrest, and they couldn’t believe it.

Some of them slipped into their fur-lined windbreakers or big red-plaided lumber jackets and drove into town to talk it over. A lot of them had known Cap all his life, still thought of him as a kid.

He looked like a kid anyway – only weighed about 155, wore his hair cut close to his head, had a big, friendly smile. They didn’t think he’d do a thing like kill Erv Kaser.

Some of them said that, even if he had, he’d been justified. Everyone knew about his divorce, and everyone knew he was a quiet, levelheaded guy who wouldn’t take the law into his own hands without good reason.

And a couple of them suggested that, if he had fired the bullets, maybe he’d just done it to scare Erv. Em Kellerhals had said the last three had come pretty fast – too fast for the killer to have taken dead aim. And a lot of people knew Erv Kaser had visited Ethel Oveross the night he died.

The next morning, a lot of Cap’s neighbors drove over to Salem and jammed into the spectator’s section of the Marion County District Court to watch Cap’s arraignment before Judge Ed Stadter.

They’d hardly gotten settled before Cap’s lawyer, Bruce Williams, asked the judge for a quick preliminary hearing so Cap could be set free. He said there was no evidence against him.

And Bruce Williams got what he wanted, partly because the cops refused to say just what the evidence against Cap was. Ed Stadter set preliminary hearing for a week later and told the cops they’d have to present sufficient evidence for him to turn the case over to a grand jury. Otherwise, he’d dismiss the charges.

Cap Oveross was very pleased. He’d sat calmly and impassively in the prisoner’s dock throughout the hearing, chewing on a wad of gum. But when Bruce Williams obtained an early hearing, he walked smiling out of the courtroom and waved to the friends and neighbors who’d come over from Silverton to see how things went.

He didn’t pay any attention when the cops returned him to the fourth cell in cellblock A of the Marion County jail, and he didn’t even look at them when they told him he could get the gas chamber in the Oregon State Penitentiary if he was convicted of killing Erv Kaser.

If Cap had known what was coming, he’d have been even more relaxed. He never even got a preliminary hearing.

District Attorney Ken Brown asked Judge Stadter if he wouldn’t send the case right to the grand jury, and the judge said yes, despite the protests of Bruce Williams.

WHAT DID JURY LEARN?

On February 28, the grand jury met in secret session at 9:30 in the morning. It didn’t finish its hearing until four in the afternoon.

And what did it learn?

It learned that Cap Oveross had refused to take a lie detector test. He said he didn’t need to, he was innocent.

According to Denver Young, it listened to several witnesses who claimed they heard him threaten Erv Kaser’s life.

It learned that some people thought he’d been at his old farmhouse the night of the killing. The cops said that was close enough to Erv Kaser’s place for Cap to have gone there and returned without any trouble.

But it didn’t learn anything about the murder weapon because it hadn’t been found after the shooting of Erv.

It didn’t learn aything about the three rifles Cap Oveross had access to because state troopers were still making tests on them in Portland.

And it didn’t learn anything about Cap’s 1950 tudor sedan because there hadn’t been much, if any, evidence in it linking him to the murder.

Seventeen witnesses were paraded in front of the grand jurors. Some were favorable to Cap Oveross, some unfavorable.

Early in the afternoon, the jurors retired to consider the evidence against the slim, boyish-looking carpenter. At four o’clock they returned and told Ken Brown and the cops there wasn’t a ghost of a case against Cap Oveross. They didn’t believe he’d killed Erv Kaser and, even if he had, there just wasn’t enough evidence to indict him.

When they brought Cap into the sheriff’s office, he was as quiet as ever. He just turned and asked Bruce Williams if it were true.

He was just as calm in front of Judge Stadter. He listened intently to the brief proceedings that resulted in his freedom and then said, “Thank you, judge” and walked out of the courtroom.

From the police, he picked up some extra clothing he’d worn when he was first arrested, four one dollar bills and his 1950 Ford. He was a free man.

Cap went back to his home and his work. He refused to say anything about his arrest or what had followed, except to repeat that he wasn’t guilty. As far as anyone could tell, even he wasn’t sure of what allthe evidence against him was.

Two days after Cap was freed, Sheriff Denver Young announced the investigation would continue. Privately, some cops admitted they didn’t know where their next clue was coming from.

More than a month after Erv Kaser died in his own blood and his own car, rumors began circulating through Silverton that the sheriff’s office had given a secret lie detector test to a suspect.

Denver Young and his aides refused to identify the suspect. As a matter of fact, they refused to admit a lie detector test had been given to anyone. They refused to deny it, too. They said they weren’t saying anything one way or the other.

Neither was the killer saying anything. But, whoever he is, he’s waiting somewhere – in the big fir country around Silverton or in Salem or in Portland or in some other state – waiting, perhaps, to strike again.

When’s Oregon going to catch him?

I’ve never heard of a “tudor sedan.” At first, I thought the author was mistaking “two-door” for “tudor.” But apparently that was actually a term that Ford once thought was cute:

“Those terms were more common in the 1939 to 1948 vehicles where they actually made a coupe, a tudor sedan, and a fordor sedan. The 1949 was the first year where they called a tudor a coupe. Ford cars continued with the business coupe in the 49 to 51 years but not for the Merc.”

Those marketing types are always pushing the envelope…

Next, I’ll be working on a time-line of events surrounding the murder. Stay tuned.

Blogically yours,

Everett